LUKE LEAFGREN

wins the 2018 Prize

"A seamless

rendering of

an outstanding

work of fiction"

The 2018 Saif

Ghobash Banipal Prize for Arabic Literary Translation is awarded to Luke

Leafgren for his translation of the novel The President's Gardens by

Iraqi author Muhsin Al-Ramli, published by MacLehose Press. The judges chose

his translation from the shortlist of four works announced on 10 December 2018.

The award of £3,000 will be presented to Luke Leafgren on 13 February 2019 at

the Translation Prizes Award Ceremony, organised and hosted by the Society of

Authors, at the British Library's Knowledge Centre, along with the other

translation prizes being awarded this year.

The judging panel

comprised publisher and translator Pete Ayrton (chair), editor and translator

Georgia de Chamberet, Jordanian author Fadia Faqir, and university lecturer and

translator Sophia Vasalou. The prize is administered by Paula Johnson, Head of

Prizes and Awards at the Society of Authors.

THE JUDGES'

REPORT

THE WINNER

Luke Leafgren for his translation of the novel

The President's Gardens by Muhsin Al-Ramli

In this brilliant

novel the personal, political and fantastical are interwoven to excavate and

record Iraq's recent history in all its complexity, horror and absurdity. The

translation by Luke Leafgren is imperceptible and mirrors the writer's many

changes of register. The author is fortunate to have found a translator totally

in sympathy with his writing. Faced with many difficult choices, Leafgren has

produced a work both faithful to the Arabic and a work of art in English.

In a clear

reference to Gabriel Garcia Márquez's Macondo, which was destroyed by the

establishment of a banana plantation, Muhsin Al-Ramli's begins his novel with

the discovery of nine banana crates, each containing a severed, mutilated head

in an Iraqi village without bananas – one of the heads belonged to

Ibrahim, "the fated", who is made sterile by poison gas in the Iran

war, loses his foot during the invasion of Kuwait and, then, finds a job in the

President's Gardens.

When Ibrahim is

appointed to "care for these roses", he is impressed with how

immaculate the garden appears on the surface - the crimes lie beneath. His job

description and responsibilities keep shifting as he descends into the inferno

until he becomes a grave-digger.

Despite Ibrahim's

fear and fatalism, he begins to give the dead a dignified burial, register the

date and time of their killing, establish and document their identity by

painstakingly gathering shreds of evidence like skin, teeth, nails, etc.

Ibrahim's acts of

salvation give a history to the thousands of Iraqi disappeared. The point is

made that ordinary people can make a difference – giving an identity to

nameless corpses ensures that they cannot be forgotten.

Tender, funny,

tragic, wise and poetic, The President's Garden is imbued with

the richness and complexity of a region that has known little peace over the

last century. Luke Leafgren's translation conveys beautifully the

spirit and idiosyncrasies of the original. It is a seamless rendering of an

outstanding work of fiction. Both author and translator are to be warmly

congratulated.

* * *

Winner Luke

Leafgren says:

"Learning that my translation was selected for the shortlist was

already the recognition that pleased me more than any other in my life,

and I've been enjoying a complicated feeling of being grateful, humbled,

proud, and inspired ever since. I am so grateful to Muhsin for writing

this novel and then entrusting me with its translation. I think of Khaled

Al-Masri, my good friend and Arabic teacher who helped me get my start in

translating. I also feel my debt of gratitude to Yousif Hanna, an

Iraqi friend who read parts of The President's Gardenswith me

to answer all my linguistic and cultural questions, and who

could become a preeminent literary scholar if he weren't committed to a

career in medicine. Finally, to Paul Engles and Christopher MacLehose, for

believing in this book and publishing the translation."

Publisher

Christopher MacLehose says:

"This is wonderful news. It gives a publisher immense pride that the

scholarship and the genius of our translator should be recognised by the jury

for your award."

ABOUT THE

WINNING TRANSLATOR

Luke Leafgren is an

Assistant Dean of Harvard College and teaches Arabic at Harvard University,

where he received his PhD in Comparative Literature in 2012. He is also a keen

sailor, and the inventor of the StandStand portable standing desk.

As well as

translating the winning novel The President's Gardens, his

first venture into literary translation was Mushin Al-Ramli's second

novel Dates on my Fingers (2014). He has also translated the

debut novel of Shahad Al Rawi The Baghdad Clock (2018), whose

Arabic original was shortlisted for the 2018 International Prize for Arabic

Fiction, and Oh Salaam!(2014) by Najwa Barakat.

On the MacLehose

Press website he describes how he came to translate The President's

Gardens.

"Muhsin Al-Ramli

was the first author I ever translated. While writing my dissertation and

needing a creative outlet, I approached one of my Arabic teachers during the

final years of graduate school to ask about how to get a start in literary

translation. My teacher told me about a friend of his who was looking for a

translator for his second novel. That friend was Muhsin, who passed through my

teacher's hometown of Irbid, Jordan, on his way from Iraq to Spain in the early

'90s. I read the novel – Dates on My Fingers – and as I was

reading the Arabic text, I could hear in my head the voice of the narrator

telling his story in English. I found myself relating to the narrator's attempt

to make sense of his place in the world, and the English translation came

through almost as quickly as I read." To continue, go to this link: https://www.maclehosepress.com/blog/2018/4/5/luke-leafgren-on-translating-the-presidents-gardens

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Muhsin Al-Ramli was born in the

village of Sudara, northern Iraq, in 1967. Since 1995 he has lived in Madrid,

Spain, where he has published 11 works – collections of short stories, novels,

a play, essays and poetry, in addition to translating some Spanish classics

into Arabic, most notably Don Quixote, and co-founding Alwaha literary

magazine. He has a PhD in Philosophy and Spanish Literature from the Autonomous

University of Madrid (2003), and teaches at the Saint Louis University, Madrid.

His three novels

to date are all translated into English: the first, Scattered Crumbs,translated

by Yasmeen Hanoosh, won the Arkansas Manuscript Translation Award; the

second, Dates on My Fingers, and third, The

President's Gardens, were both translated by Luke Leafgren, with both

their Arabic originals being longlisted for the International Prize for Arabic

Fiction (IPAF, aka Arabic Booker Prize) in 2009 and 2013 respectively. His

novel-in-progress, Qisma's Fate, a follow-up to The President's

Gardens, and also being translated by Luke Leafgren, is due out later

this year.

Muhsin Al-Ramli

writes on the MacLehose Press website about how he came to start writing the

book in 2006. "I began writing The President's Gardens in

2006 after receiving the news of the murder of nine of my relatives, who were

fasting on the third day of Ramadan. The people of the village found only their

heads in banana crates, along with their identity cards. I dedicated the novel to

their souls. It was a huge shock to me. It horrified me, and, to start with,

the novel was a reaction to this event undertaken without planning or a clear

vision."

ABOUT THE WINNING TRANSLATION

The President's

Gardens

MacLehose Press (20 April 2017),

Paperback edition: 352 pages

ISBN 9780857056788

The translated

novel The President's Gardens has already been much reviewed

and talked about since publication in 2017. Its Arabic original

sold well and was longlisted for the International Prize for Arabic Fiction in

2013. It also has a Spanish edition Los Jardines Del Presidente.

Buy a copy in UK

Buy a copy in US

EVENTS:

• TRANSLATION

PRIZES AWARD CEREMONY

7.00pm Wednesday 13 February

The Knowledge Centre, The British Library, 96 Euston Rd, London NW1 2DB

Hosted and

organised by the Society of Authors, who administer all the prizes, the

ceremony will award prizes for translation from Arabic, French, Italian German

and Spanish and the Translators' Association First Translation Prize. https://www.societyofauthors.org/Prizes/Translation-Prizes

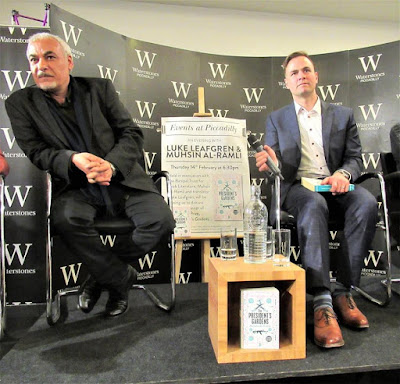

• AN EVENING

WITH LUKE LEAFGREN AND MUHSIN AL-RAMLI

Discussions,

Readings and Q&A ............... and refreshments

6.30pm Thursday 14

February, Lower Ground Reception, Waterstones Piccadilly,

London W1V 9LW

This is a free event, but places must be booked to avoid disappointment. Please

register here on the Waterstones Piccadilly

Events special webpage.

* * *

The 2018 Prize – The Shortlist

The Saif Ghobash

Banipal Prize is delighted to announce the shortlist of the 2018 Prize. The

four works are translated by two former winners of the prize, Khaled

Mattawa and Jonathan Wright, and two relative newcomers to

literary translation Ben Koerber and Luke Leafgren.

The judges were

impressed by the tremendous variety of the entries from different parts of the

Arab world, ranging through poetry, crime, literary fiction and graphic novels.

The shortlist reflects this diversity, with two novels about the wars in Iraq

and their aftermath, a collection of poetry about Jerusalem, and a contemporary

take on Cairo today. In the face of social and political upheaval, literature

continues to make waves in the Arab world.

Using Life by Ahmed Naji

(Egypt),

translated by Ben Koerber (CMES Publications, University of

Texas at Austin)

The President's

Gardens by Muhsin Al-Ramli (Iraq),

translated by Luke Leafgren (MacLehose Press)

Concerto al-Quds by Adonis

(Syria),

translated by Khaled Mattawa (Yale University Press)

Frankenstein in

Baghdad by Ahmed Saadawi (Iraq),

translated by Jonathan Wright (Oneworld)